From: Jailgoldendawn

Αναδημοσιεύουμε μια αναλυτική μελέτη της δίκης της ναζιστικής τρομοκρατικής οργάνωσης NSU από την δικηγόρο πολιτικής αγωγής Antonia von der Behrens. Θυμίζουμε – μιας και το κείμενο δεν περιλαμβάνει την τελική απόφαση του δικαστηρίου – ότι η Μπεάτε Τσέπε καταδικάστηκε ισόβια για συναυτουργία σε δέκα ανθρωποκτονίες, ένταξη σε τρομοκρατική οργάνωση και εμπρησμό. Ο Ραλφ Βολέμπεν που κατηγορούταν για απλή συνέργεια-συνδρομή σε εννιά ανθρωποκτονίες καταδικάστηκε σε δέκα χρόνια κάθειρξη. Ο Άντρε Έμινγκερ καταδικάστηκε σε δυομισυ χρόνια φυλάκιση και ο Χόλγκερ Γκέρλαχ σε τρία χρόνια φυλάκιση για το αδίκημα της συνδρομής σε δράση τρομοκρατικής οργάνωσης. Ο Κάρστερ Σούλτσε καταδικάστηκε για απλή συνέργεια-συνδρομή σε εννιά ανθρωποκτονίες, αλλά η ποινή του περιορίστηκε στα τρία χρόνια φυλάκισης λόγω τέλεσης του αδικήματος στη μετεφηβική ηλικία.

Summary of Political, Social and Legal Aspects of the Case Against the National Socialist Underground (NSU) – as at July 3rd, 2018.

by Antonia von der Behrens [1].

I. Trial Overview

The judgment in the so-called NSU trial is expected to be heard on Wednesday July 11th, 2018, following 437 days of trial. [2]

Since May 6th, 2013, five defendants have been standing trial before the Munich Court of Appeals [3]. They are accused in connection with crimes committed by the neo-Nazi terrorist organization “National Socialist Underground” (NSU). The main defendant, Beate Zschäpe, faces life imprisonment and the other defendants sentences of up to 10 to 15 years. More than 95 family members of victims or the victims of the NSU crimes have joined the proceedings as private accessory prosecutors. Almost 600 witnesses have been heard during the trial[4]. The closing arguments of all the parties to the proceedings – prosecution, defense and lawyers for the victims – took almost the whole of last year. On July 3rd, 2018 four of the five defendants used their procedural to address the court directly. Barring the unexpected, the judgment is set for July 11th, 2018. The judgment will include the verdict, the court’s finding of guilty or not guilty, and sentencing. The grounds for the judgment will be given orally by the presiding judge, Manfred Götzl, and will take about a whole trial day. The much longer written judgment will be issued later. This can take many months or even over a year to complete. The defense, the federal public prosecutor, and the private accessory counsel – in the event of a partial acquittal – have one week after the oral delivery of the judgment to file their appeal if they wish to do so. The legal grounds for the appeal have to be filed after the written judgment has been delivered. The judgment will only be reversed by the Federal Court of Justice if it finds that the trial court has made mistakes in applying the law or procedural errors during the trial. Even though the defense has asked for the acquittal of three of the five defendants, it seems most likely that they will be found guilty on all counts.

On July 11th, the day of judgment, there will be a demonstration in Munich called “Kein Schlussstrich” [5] as well as local demonstrations across Germany demanding that light continue to be shed on the NSU complex even after the judgment.

II. Contents

1. Introduction

2. Crimes of the neo-Nazi Terror Organization NSU

a) Crimes committed by the NSU

b) A short historical background of the radicalization of NSU members and supporters

3. Police investigations into the crimes committed by the NSU

a) Investigations before November 4th, 2011

b) Specific questions concerning two of the murders

c) Investigations after November 4th, 2011

4. Reactions to the discovery of the neo-Nazi terror cell in 2011 and the following years

a) Society and media

b) Political reactions

c) Resignations in the aftermath of the discovery of the NSU

d) Parliamentary inquiry committees

e) Disciplinary measures and criminal investigations against civil servants

f) NSU: no discursive event

5. The case against Zschäpe and others before the Munich Court of Appeals [6]

a) Overview of the court and the parties

b) German criminal procedure

c) The federal public prosecutor and its indictment

aa) The indictment

bb) Evidence

d) The defense and defense strategy

aa) Defendant André Emigner

bb) Defendant Holger Gerlach

cc) Defendant Carsten S.

dd) Defendant Beate Zschäpe and her testimony of December 2015

ff) Defendant Ralf Wohlleben

e) The victims: private accessory prosecutors

f) Witnesses

g) Closing arguments

aa) Federal public prosecutor

bb) The private accessory counsel and the victims

cc) The defense

6. Summary and outlook

1. Introduction

The German neo-Nazi terrorist organization, the National Socialist Underground (NSU) committed ten murders, three bomb attacks, and 15 bank robberies in the years between 1998 and 2011. They did not claim responsibility for their crimes and were not discovered by law enforcement until November 4th, 2011.

The so-called NSU complex has been called one of the biggest “failures” of German law enforcement and secret services by politicians and the mainstream media. These failures were allegedly caused by individual “mistakes” and a lack of coordination and competition between the responsible authorities [7].

From a progressive perspective, the NSU complex is an unprecedented example of the close connection [8] between the secret services and the neo-Nazi movement, as well as structural racism within the law enforcement authorities.

The complex raises three main questions:

-

- Why was it that until 2011, the year in which the NSU brought about its own detection, even progressive parts of German society widely underestimated the extent of right-wing/neo-Nazi terror? And why was it thought that something like the NSU would not be possible, given Germany’s history of right-wing terrorism since the 1950s and pogrom-like mob violence against refugees since the 1990s?

- What was and is the overall role of the police and the secret servicesix in building the neo-Nazi scene, especially through its informants, who held and hold high-ranking positions in neo-Nazi organizations? And what did the secret services know about the existence of the NSU, its crimes, and the whereabouts of its members and supporters? [10]

- What is the extent of structural and institutional racism in Germany? What mechanisms does it use? And how did it allow law enforcement agencies to attribute the crimes of the NSU to the “Turkish mafia” and organized crime rather than to neo-Nazis? What is the state’s ability and willingness to protect immigrant communities from racially motivated terrorism?

- To what extent is the ideology of the NSU and its support network rooted in racist and anti-refugee and especially anti-Turkish sentiment and discourses within mainstream society in the 1990s? To what extent do the right-wing movements of Pegida [11] or the right-wing party Alternative for Germany (AfD) share elements with a right-wing terrorist organization like NSU? In other words, do we have to deal with everyday racism in order to fight the gaining strength of right-wing and authoritarian movements? And how does the NSU fit into broader patterns of right-wing in Europe? [12]

On the political level, 13 parliamentary inquiry committees have been established to investigate the NSU complex and consider possible consequences. Of these 13 committees, eight have finished their work and five are currently still working. In addition, special rapporteurs and investigators have conducted investigations on federal and state level, especially with regard to the destruction of files and the work of informants (see para 3.c).On the judicial level, the federal public prosecutor has so far only brought the current case pending in front of Munich Court of Appeals against the five defendants. It is the biggest and one the most important trial against neo-Nazis in Germany since the Second World War.

Despite these ongoing parliamentary and judicial investigations, the questions posed above are far from being answered and will most likely remain so for some time. This paper aims to provide a very general introduction to the topic and explain why the NSU case raises these questions. Over the course of the investigation more and more questions have been raised and very few have been answered. Therefore, this paper can only provide a basic overview and refer the reader to links for further reading.

After a brief synopsis of the case, this paper will describe the police investigations and discuss the reactions of society and various actors, before setting out an overview of the ongoing court case.

2. Crimes of the neo-Nazi terror organization NSU [13]

The existence of the neo-Nazi terror organization National Socialist Underground (NSU) only came to light after the suicide of two of its members, Uwe Mundlos and Uwe Böhnhardt, after a botched bank robbery in Eisenach, Thuringia on November 4th, 2011. Only hours later, the third alleged [14] member, Beate Zschäpe, allegedly set fire to their shared apartment at the address Frühlingsstraße 26 in the city of Zwickau, Saxony in order to destroy evidence. The fire caused an explosion, potentially endangering the lives of three people. Four days later, on November 8th, Zschäpe turned herself in to the police in Jena. In the meantime she had driven across Germany and allegedly distributed several DVDs with a video in which the NSU claimed responsibility for ten murders and two bomb attacks [15]. This video was shocking and horrific, using the cartoon figure the Pink Panther to cynically illustrate the murders. [16]

In the following days, it became apparent that Zschäpe and her two male co-conspirators had lived underground since 1998. On January 26th, 1998, the police raided a garage in Jena, Thuringia where the three had stored 1.4 kg of TNT and had built several pipe bombs, for which only the detonators were missing. At that time they were already well known to the authorities as very active and radical neo-Nazis pursuing racist, anti-Semitic and neo-National Socialist ideas.

They were organized in the so-called Thuringia Home Guard (Thüringer Heimatschutz [THS]), a neo-Nazi organization founded in 1994, which was a loose part of a German-wide network of militant neo-Nazis. The Thuringia Home Guard was led by Tino Brandt, an informant for the domestic secret service of Thuringia.

After the 1998 raid on the garage in Jena, Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe, all in their early twenties at that time, were able to flee. With the help of neo-Nazi comrades from the Thuringia Home Guard and Blood and Honour Saxonia they assumed false identities and lived in the state of Saxony for the next 13 years, allegedly evading detection.

During that time, according to the indictment of the federal prosecutor, Mundlos, Böhnhardt and Zschäpe founded the terrorist organization National Socialist Underground, whose main aim was to kill migrants, especially of Turkish [17] origin. They called these migrants the “enemies of the German nation” and hoped to spread fear within their communities. In line with their ideological belief and their tactical course of action to spread their message through their actions, they did not claim responsibility for their crimes in any way.

a) Crimes committed by the NSU

According to the indictment of the federal prosecutor in the case against Zschäpe and others the NSU is responsible for murders, bomb attacks, and robberies:

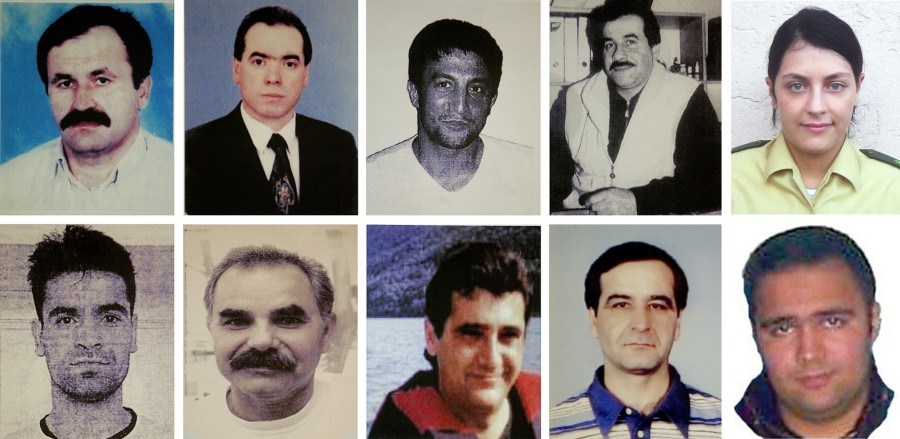

- The NSU committed ten murders between 2000 and 2007. The victims were eight men of Turkish and Kurdish origin, one man of Greek origin and one policewoman of German origin: Enver Şimşek [18] (killed in 2000, in Nuremberg), Abdurrahim Özüdoğru (2001/Nuremberg), Süleyman Taşköprü (2001/Hamburg), Habil Kılıç (2001/Munich), Mehmet Turgut (2004/Rostock), İsmail Yaşar (2005/Nuremberg), Theodoros Boulgarides (2005/Munich), Mehmet Kubaşık (2006/Dortmund), Halit Yozgat (2006/Kassel) and Michèle Kiesewetter (2007/Heilbronn). All nine of the victims of non-German origin were shot execution-style with the same weapon, a Ceska 83 pistol with a silencer. This quickly enabled the police to consider these murders as part of a series. The victims were apparently chosen randomly, the only criterion being that they were, in the racist understanding of the NSU, actually or seemingly of Turkish origin. They lived in different German cities and were all proprietors of small shops and businesses. The last murder took place in 2007: The police officer Michèle Kiesewetter was shot and killed and her colleague was shot in the head and severely injured. At the time of the attack they were on duty in the city of Heilbronn, sitting in their police car having lunch. This crime is determined by a different and still unclear motive. The indictment sees it as an attack on representatives of the German state. The police officers were not shot with the Ceska 83 pistol, but with two other weapons. Therefore, this murder was not considered as part of the series until 2011. The modus operandi of all ten murders was always identical; the victims were shot in their shops, or in the case of the police officers in their car, and the offenders fled on bikes. The bikes were later loaded into a parked caravan and hidden there or left behind in the city.

- The NSU committed three (nail) bomb attacks aimed at migrants.

According to the testimony of the defendant Carsten S. [19] the first bomb attack took place in Nuremberg, Bavaria on June 23rd, 1999, wounding the Turkish proprietor of a bar. The bomb, which was hidden in a flashlight, exploded, but did not function as the perpetrators had intended. Were it not for this malfunction, the victim would surely have been killed.

The second attack happened on January 19th, 2001, in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia. A bomb was hidden in a box for Christmas cake that was seemingly forgotten in a grocery store run by an Iranian couple. Their daughter, who opened the box and thus triggered the explosion, was lucky to survive and suffered severe burns, particularly to the face.

The last known attack was carried out on June 9th, 2004, again in Cologne. The bombing took place on Keupstraße, an area inhabited by many people of Turkish and Kurdish origin, with numerous shops and restaurants owned by members of this community. The bomb was placed on a bicycle, which was then left in front of a barbershop. It contained a large amount (at least several kilos of gun powder), as well as 800 nails, each 10 cm in length, rather similar to the bomb used in an attack in London in 1999 by neo-Nazi David Copeland. Again, it was only by chance that no one was killed. Many people, however, were severely injured (23 wounded all together)[20] and many more were traumatized.

- The NSU committed a total of 15 robberies of banks, post offices and one supermarket in the years between 1998 and 2007 and in 2011. These were aimed at financing the operations of the organization. During these robberies one bank customer and one passerby were shot; both survived.

The NSU only claimed responsibility for the murders and the two bomb attacks in Cologne after the death of Uwe Böhnhardt and Uwe Mundlos, by way of the aforementioned video allegedly sent out by Beate Zschäpe after she had set fire to their hideout in 2011. But they later acted in ways that suggest they wanted police to understand that the murders and bomb attacks targeted Turkish migrants and that the murders and bomb attacks were carried out by the same perpetrators. The bomb attack on June 9th, 2004 on Keupstraße in Cologne so clearly had all the hallmarks of a random attack on the people who lived and worked on the street that it is unintelligible that from the beginning of the investigation the police rejected the notion that this could have been a terrorist attack. It seems the members of NSU were themselves astonished about this and reacted by committing their next murder, of Ismail Yasar, exactly one year later, on June 9th, 2005. Despite the matching dates, the police did not made a connection between the murders series and the bomb attack. Only two years later a witness pointed out that the description of the perpetrators of the murder and the bomb attack on Keupstraße were similar. The police were quick to dismiss her statement and never followed up on the lead.

Between 1998 and 2011, while committing the crimes the three members of the organization, Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe, lived in the cities of Chemnitz (January 1998 until June 2000) and Zwickau (July 2000 until November 2011), both in Saxony and only about 100 km from Jena, from where they had initially gone underground. They were aided and abetted by a large number of neo-Nazis and by the neo-Nazi network Blood and Honour [21], who provided accommodation, passports, medical aid and even tried, in some cases successfully, to procure weapons for them. Some of the neo-Nazis in this support network were police or intelligence service informants and many more informants existed in their wider networks as associates or friends of friends. The most important informants were Tino Brandt [22] and Marcel Degner [23], who worked for the domestic secret service of Thuringia, Carsten Szczepansk [24], who worked for the same organization in the state of Brandenburg [25], and Thomas Richter [26] and Ralf Marschner [27], who work for the federal secret service. The services claim that neither they nor other informants provided information about the terrorist organization NSU or information that would have been sufficient to arrest Zschäpe, Böhnhardt, and Mundlos.

Even while underground, and especially in later years, Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe led quite comfortable lives, for example spending money from the robberies on long vacations or pursuing expensive sports.

To this day it is still unknown whether the NSU organization had more than three members. However, the federal prosecutor always spoke of three members and only admitted in his closing arguments in summer 2017 that André Eminger might be a fourth member but that they did not have enough evidence to prove it.

Very little information existed about the terrorist organization until 2011. The intelligence services and law enforcement deny ever having heard of the existence of such an organization before November 2011. However, there are strong indications that this is not true and that they had access to information concerning an organization called the NSU. It is known, for example, that in 2002 the NSU sent a one-page letter, the so-called NSU letter, to several Nazi publications and organizations, introducing its underground organization. The letter read: “The National Socialist Underground embodies the new political force in the struggle for the freedom of the German Nation … Loyal to the motto ‘Victory or Death’ there will be no reverse. … The NSU will never be contacted through an address, which does not mean however that it is unapproachable. Internet, newspapers, and zines are excellent sources of information even for the NSU.” Enclosed with these letters was a sum of money, loot from the bank robberies, to support these organizations. As a reaction to this letter, one magazine printed a thank you note to the NSU – something the intelligence services definitely knew about. In the video in which the NSU claimed responsibility they referred to the NSU as a “network of comrades with the principle deeds instead of words”.

b) A short historical background of the radicalization of NSU members and supporters

Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe were radicalized as teens and young adults in the early 1990s in Jena, a small university town in Thuringia, one of the former states of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

During the 1980s neo-Nazis in West Germany had tried to organize themselves in different parties and organizations. After some of these were banned, they resorted to so-called independent comradeships (Freie Kameradschaften) under an umbrella organization.

After the unification of East and West Germany in 1990, the neo-Nazi scene in both parts of Germany experienced a boom. The West German neo-Nazis exported their model to the East, where comradeships also sprang up. Others joined the legal neo-Nazi party, National Democratic Party of Germany (Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands [NPD]), which led to conflicts within the party as to the course the party was to take.

At the same time seemingly unorganized attacks by neo-Nazis were also on the rise. Those who were attacked did not correspond to the perpetrators’ world view, in particular migrants and refugees. Some of these attacks were openly supported by average citizens. The worst of these pogroms, which killed and severely injured many people, happened in the German cities of Hoyerswerda (1991), Rostock-Lichtenhagen (1992), Mölln (1992) and Solingen (1993). From 1990 until 2013, 184 people were killed for right-wing motives in Germany. [28] The neo-Nazis also achieved one of their main aims in that the individual right to asylum as defined in the German constitution was severely curtailed and the rights of refugees were severely limited by reforms in 1994.

In the mid-1990s, the British based neo-Nazi organization Blood and Honour formed a “division” in Germany. Some Blood and Honour members established a militant arm of the organization called Combat 18. A widespread debate sprang up within the ranks of Blood and Honour, including Blood and Honour Germany, about the methods employed by Combat 18. The German neo-Nazis translated the two Blood and Honour pamphlets, The Way Forward (1998) and The Field Manual (2000), into German. These pamphlets featured concepts of armed struggle, such as Combat 18, the ideological concept of white supremacy, the organizational concepts of leaderless resistance, and a right-wing form of propaganda-of-the-deed. The Way Forward also discussed the Swedish so-called laserman, who killed one person and wounded eight others out of racist motives without claiming responsibility for the crimes [29]. These concepts were discussed within the German neo-Nazi scene. Similarly, the original source of the concept of leaderless resistance, the Turner Diaries and the Hunter were also discussed. Both written by William L. Pierce, they were published in 1978 and 1989, respectively, and depict a dystrophy of right-wing terrorism aimed at causing a civil war between white and black US-Americans.

There was a connection between such discussions and the general radicalization of the neo-Nazi movement at the beginning of the 1990s. This radicalization and militarization became apparent to law enforcement agencies, who, when conducting searches of homes of neo-Nazis, regularly found firearms and bombs. This dangerous situation was aggravated by German neo-Nazis returning with combat experience from the Yugoslavian civil war.

It was in this political situation and climate that the members of the NSU and their supporters were radicalized. It was also this climate which led them to think of themselves as members of a growing movement. Thus, it was likely they believed their racist attacks would find support amongst the average German populous, and furthermore that there were people within the neo-Nazi movement who could be organized and radicalized by their acts.

The NSU was not alone, and several other neo-Nazi terrorist groups founded during the 1990s and early 2000s also plotted and committed attacks. Seemingly due to informants tipping off the authorities none of these groups were able to grow significantly. However, this pattern was not true for the NSU insofar as although there were many informants close to the group, allegedly none of the information gathered was enough for the authorities to locate them.

3. Police investigations into the crimes committed by the NSU

a) Investigations before November 4th, 2011

The police investigations into the crimes were carried out by many different state police authorities and were not centralized by the federal police.

The police authorities never saw a connection between the murders of nine migrants executed with the Ceska 83, the murder of the policewoman, the three bomb attacks, and the robberies. [30]

Regarding the nine murders of migrants with the same weapon, the investigations focused almost exclusively on the victims and their alleged and actually non-existent ties to organized crime, the “Turkish mafia”, drug dealing, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and so on. In the murder cases where police investigated the possibility that these acts might have had right-wing motives, they did so only in a very superficial manner, and leads in this direction were hardly ever followed up. The constant failure of the police authorities to solve the murders was attributed to the Turkish and Kurdish background of the victims and the supposed unwillingness of their family members to cooperate with the police. The “evidence” supporting this claim was that each family had repeated to the police that they had no idea who could possibly have wanted to kill their father or brother. The police had only one explanation for the apparent lack of information forthcoming from the families: that they lived in a “parallel society” with their own sets of values, which prevented them from speaking with the police. These allegations were both wrong and distressing for those involved, as the families were questioned by the police repeatedly, often for whole days at a time. Furthermore, the families cooperated fully with the police investigations, turning any information they had over to police in the hope this would help to find the murderer. They disclosed information relating to their financial situation, private problems, and even information on distantly related cousins in Turkey that the police were interested in.

Most of the victims’ families, having not only suffered the murder of their loved ones and not knowing who the murderer was, now found themselves attacked by police investigations and the media. Furthermore, the reputations of the dead men and their families were sullied, as they were from then on associated with organized crime. Even when the victims’ families asked the police to consider the possibility of a right-wing motive for the crime, this was to no avail. Additionally, the police authorities ignored a Criminal Investigative Analysis, which had been conducted by the FBI at the request of the German police. This analysis came to the conclusion that the victims were killed “because they are of Turkish ethnic origin”. However, these findings failed to trigger any serious investigation into the validity of those claims [31].

Most of the media accepted the police information uncritically as the basis for their reporting. They were mainly responsible for spreading the allegations that the Turkish mafia or similar groups were responsible for the crimes and that the families were refusing to cooperate with the German police. The term “Dönermorde” (“Döner kebab murders”) coined by the German media particularly shows the racial connotation that the reporting of the murders had, as this soon became the catchword to refer to the series of murders [32]. The perception of the murders as an internal problem for the Turkish community and the stigmatization of the victims’ families were partly due to the media’s coverage of the crimes. The tenth murder, of the policewoman, was not seen as part of the series, since she and her colleague were shot with a different weapon.

The same pattern can be seen in the investigations into the bomb attacks. In all three cases, which the police did not regard as connected, the police looked for suspects close to the victims or in connection with organized crime, and neo-Nazi suspects were never seriously considered. In the case of the bomb attack in Keupstraße in Cologne, the police denied the terrorist nature of the attack, and yet again the bombing was attributed to organized crime. This public denial contradicted the internal analysis of the secret service and the police, according to which there may have been a racist motive behind the crime. The once lively shopping street that is Keupstraße also experienced an economic decline as tourists and people form other parts of the city were afraid to go there. Since many victims of the bomb attack were small shop owners, they were particularly affected by this. Furthermore, given the severe consequences for the victims of the attack in Keupstraße, the investigations were later referred to as the “bomb after the bomb”.

Most of the 15 robberies were believed to be connected, as the offenders were always two young men seen fleeing the crime scene on bikes. But no connection was ever made between the robberies and the murders and/or bombings, despite the fact that many witnesses had seen two young men with bikes close to the scenes of the respective crimes.

As it was unknown who was carrying out the murders and the bombings, these attacks spread fear within the Turkish and Kurdish community, which was obviously what the perpetrators had intended. After the eighth and ninth murders, family members organized a demonstration in the cities of Kassel and Dortmund calling for a thorough investigation into the spate of killings [33]. Almost all of those who took part in this demonstration were also members of the community to which the victims belonged.

b) Specific questions concerning two of the murders

The circumstances of the last murder, that of a Turkish man, Halit Yozgat, in Kassel, Hesse on April 6th, 2006, are particular noteworthy [34]. He was shot in the head in his Internet café while several customers were present on the premises. One of these “customers” was Andreas Temme, a Hessian domestic secret service agent. Temme did not inform the police of his presence at the crime scene, but was tracked down by police through a witness statement and the login data from the computer he had used. Temme was arrested two weeks after the murder and questioned for one day. To this day, this secret service agent denies having witnessed the murder or having heard the gunshot being fired, which is almost impossible since the investigation revealed that there was not enough time for Temme to have left the café before the murder was committed. As to his reasons for failing to notify the police, he claims that as a secret service agent he was not supposed to be in that particular Internet café and that he was embarrassed as he, a married man, had been surfing dating websites.

Of course Temme’s presence at the crime scene raises many questions, all the more so given that he was in charge of two informants on the Kassel Nazi scene. Temme and one of his informants by the name of Benjamin G. talked on the phone for more than 15 minutes just before the murder.

The victims’ families are not the only ones who believe it more than likely that the secret service agent was aware of information indicating that something (possibly even a murder) was going to happen. Furthermore, there is evidence that Temme knew the brand of the murder weapon before that information became public. In the aftermath of his arrest in 2006, the Hessian secret service tried to protect Andreas Temme and to control the police investigation. A leading member of the homicide division that investigated the murder of Halit Yozgat testified before the court that he was convinced Andreas Temme either saw the murderers or was in some way involved in the crime himself [35]. The question of why Andreas Temme was at the crime scene, what he saw, and what he possibly knows about the murder of Halit Yozgat are vital and lead to the parliamentary inquiry of the Hessian parliament. So far these questions remain unanswered. [36]

The final crime in the series of murders, the murder of policewoman Michèle Kiesewetter and the attempted murder of her colleague in Heilbronn, Baden-Wuerttemberg in 2007, also raises many questions, not least about the reason for the murder. They were both shot in the head while sitting in their car having lunch at Theresienwiese in Heilbronn, a large area that was being used for a fun fair. The perpetrators not only shot them, but also took their service weapons and other pieces of equipment. Unlike all the other murders there was no investigation into the families of the police officers but instead extensive investigations into a group of Roma who were at the fairground. They became a main focus of the investigation and some members of the group were traced throughout Europe, without any hard evidence that they had anything to do with the crime. Only in 2011 did it become apparent that the NSU had committed the crime and also that there were connections between the NSU, its supporters and the murdered police officer, who came from a small town in Thuringia. To this day, the federal prosecutor is of the opinion that there were no ties between her and the NSU and that it was pure coincidence that Michèle Kiesewetter was from Thuringia. In order to answer this and many more questions surrounding the murder a parliamentary inquiry committee was set up in the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. In its finding it comes to the conclusion that Michèle Kiesewetter was chosen randomly and was killed for being a policewoman.

c) Investigations after November 4th, 2011

It was only after November 4th, 2011 that it became known that neo-Nazis were responsible for this unprecedented series of crimes.

The official criminal investigation of the case after November 4th, 2011 was carried out by the office of the federal prosecutor (Generalbundesanwalt [GBA]) and the federal criminal police (Bundeskriminalamt [BKA]). In the indictment of November 2012, the federal prosecutor claims that the NSU consisted solely of an isolated cell of three people, with no others having had direct knowledge of the crimes, and without any involvement from the secret services or its informants. The investigations are ongoing and a small task force of the federal criminal police are investigating the case against the five defendants before the Munich Court of Appeals. Furthermore, an additional nine other suspected supporters of the NSU and an unspecified number of potential supporters are under investigation. One of the task force’s main assignments is to investigate where the 20 weapons used by the NSU came from. So far the federal prosecutor has denied the victims and their lawyers access to these case files.

It was primarily the work of investigative journalists and parliamentary inquiry committees that brought to light the following facts:

- Many grave “mistakes” made during the search of the garage in Jena on January 26th, 1998 and the police manhunt that ensued raised the question as to whether the three suspects intentionally went underground or whether the authorities were simply not interested in finding them.

- Many high-ranking and influential neo-Nazis were informants of the domestic secret service. They reinvested part of their earnings as informants in the neo-Nazi scene and were warned of house searches due to be conducted by the police. What is more, it is unclear to what extent the domestic secret service agencies acted upon the information of their many informants regarding the whereabouts and activities of Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe in the years between 1998 and 2011. There is evidence that the secret services knew of their whereabouts and activities. At the very least they made no contribution to bringing about their arrest. However, a careful consideration of the case, which could put all the pieces together and point to the gaps in the official story has been made difficult by the many conspiracy theories surrounding the case. The question of the knowledge and the role of the secret service especially the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz [BfV]) has been at the center of the two federal parliamentary inquiry committees.

- Related intelligence files on seven informants within the neo-Nazi scene, which Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe were part of, were purposely destroyed by the federal domestic secret service on November 11th, 2011, just after the crimes of the NSU had come to light. [37] Among them was the file of the informant Michael See [38], who had been asked to help hide Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe after they had gone underground. To date, neither the parliamentary inquiry committees nor expert groups have been able to provide convincing explanations for the destruction of the files. In addition to these files, many more relevant files which had been kept by different secret service authorities were destroyed before the summer of 2012. At that time, the destruction of the files on November 11th, 2011 became known, and after a public outcry a moratorium was issued stipulating that no potentially relevant files should be destroyed until investigations were complete.

4. Reactions to the discovery of the neo-Nazi terror cell in 2011 and the following years

a) Society and media

After the exposure of the NSU and its crimes in 2011, there was complete bewilderment that a neo-Nazi terror organization could live and commit crimes in Germany and go undetected for 13 years. Society had to realize that (neo-)Nazi terror in the Federal Republic had existed since the 1950s [39] but had never been assessed as being an imminent danger, at least not by the general public. Antifascist organizations, which had for years been sounding the alarm that neo-Nazis were being underestimated and that new terrorist structures were in the process of being built in the 1990s, had simply not been heard.

Subsequently a debate arose about the secret service ignoring the possible threat from right-wing groups. Credit must be given to two German journalists, Stefan Aust and Dirk Laabs, who showed in their book, Homeland Security (2014),[40] that the domestic secret service was well aware of right-wing terrorist structures and had informants close to or within these organizations. Nonetheless, the secret service claimed not to have known about the NSU or its activities.

b) Political reactions

On February 23rd, 2012, an official state ceremony in commemoration of the victims was broadcast live from Berlin; there was a nationwide moment of silence, flags flown at half-mast. Chancellor Merkel herself delivered the main speech and officially apologized for the poor police work and pledged that everything would be done to get to the bottom of the questions surrounding the NSU. She stated:

“As Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany I promise you that we will do everything to solve these murders, to identify all those behind them and to ensure that everyone involved is given their due punishment. All the relevant agencies at regional and national level are working with urgency on these cases. This is of great importance, but it is not enough on its own. For we also have to do everything consonant with the rule of law to ensure that something like this can never happen again.” [41]

Many of the victims and family members hold the actions of the agencies up against Merkel’s so-called “Aufklärungsversprechen” (the unfulfilled promise to lift the lid on the NSU complex/the NSU’s crimes).

However, structural racism within the police force was not acknowledged. In the following period of time the victims’ families were invited to meetings with two German presidents. They were granted a very small monetary “compensation” in the amount of 10,000 Euros for close relatives of murder victims and 5,000 Euros for other NSU victims. Furthermore, a so-called “ombudswoman for the victims” was installed by the Government [42]. Many of the victims feel rather betrayed by these official acts. The thorough investigation promised by the German Chancellor on February 23rd, 2012 has not truly taken place and only very few victims have been called to testify before any of the many parliamentary inquiry committees.

c) Resignations in the aftermath of the discovery of the NSU

The uncovering of the NSU also led to the resignation of several high-ranking public officials in the secret services, including the head of Germany’s federal domestic secret service and the heads of three state services. [43] These resignations, however, were mostly for public image, as can be seen by example of the career of Gordian Meyer-Plath, who took over the position as head of the domestic secret service of Saxony when its former president resigned in connection with NSU case. Meyer-Plath, however, was himself not without involvement in the NSU case, as he had been a secret service employee in the state of Brandenburg. In that position he was responsible for one of the most important neo-Nazi informants, the aforementioned Carsten Szczepanski, from whom he had personally received important information on the whereabouts and activities of Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe in 1998, information the service never passed on to the police so as to lead the police to the whereabouts of the NSU.

d) Parliamentary inquiry committees

As stated above, 13 parliamentary inquiry committees (Parlamentarischer Untersuchungsausschuss), four of which are currently still working, were set up to investigate the NSU case and consider possible consequences [44].

The first federal parliamentary inquiry committee was set up by the federal parliament (Bundestag) in 2012 to look into the “systemic failure” of the police and domestic secret service. After consulting roughly 12,000 documents and questioning over 100 witnesses, it published its final report, some 1,300 pages in length, on August 21st, 2013. The report contains the first information to be published about the NSU, its network, the investigations and the acts and omissions of the domestic secret services. In its more political conclusions on topics such as the responsibility of law enforcement and the domestic secret service or on the issue of structural racism, however, the report is rather lacking [45]. The committee’s 47 recommendations have so far only led to new laws strengthening the law enforcement authorities on the federal level and the federal domestic secret service [46]. After some political struggle the Bundestag decided to set up a second parliamentary inquiry committee at federal level in November 2015 in order to investigate the NSU complex further. Since the closure of the first committee much new information regarding the secret services and their role has emerged, and it came out that they had withheld many files as well as crucial information. The report of the second committee is due this year.

In addition, several parliaments of the German states in which one or several NSU murders were committed have also set up parliamentary inquiry committees. Some states have also established a second committee after receiving the report of the first. All of their final reports have in common that they focus on the failure of the authorities in terms of “mistakes” rather than structural problems or even intention. An exception is the very thorough work and resulting report of Thuringia’s first parliamentary inquiry committee. One of the findings in the 1,800-page report is that there is strong evidence of direct obstruction and deliberate thwarting of the police search for the three fugitive Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpex [47].

In addition, several official reports were prepared by special rapporteurs (Sonderermittler) investigating single aspects of the case, such as the destruction of the intelligence files and the sudden death of Thomas Richter, a secret service informant who passed on information on Uwe Mundlos and possibly the NSU, hence his death receiving particular scrutiny.

e) Disciplinary measures and criminal investigations against civil servants

Although the police officers and secret service members involved in the investigation did not explore alternative explanations for the series of murders before 2011 there were no disciplinary measures against them. This was despite the clear omission and overlooking of evidence that would have led to the investigation of alternative explanations for the crimes.

The aforementioned (see para 3.c) destruction of files by the federal domestic secret service on November 11th, 2011, has been at the heart of criminal investigations into a possible cover-up. After the destruction became public, many lawyers for the victims, NGOs, and private persons filed complaints with the police and asked them to open criminal charges due to the suppression of documents and the obstruction of punishment. These charges were to no avail. The public prosecutor in Cologne closed the preliminary investigation on the grounds that there was no evidence the files were destroyed with criminal intent. Exploring questions about the destruction of files and the motives behind the act was one of the tasks of the first federal parliamentary inquiry committee. However, it was only at the end of the second federal parliamentary inquiry committee that it became known that Lothar Lingen (pseudonym), who ordered the destruction of the files, had admitted to the federal prosecutor that he had destroyed the files on purpose. His account is that he wanted to protect the federal secret service from tough questions as to why they supposedly did not know about the murders and the existence of the NSU if they had many informants close to Mundlos, Böhnhardt, und Zschäpe. After that testimony came to light in the fall of 2016 there was a new push for a criminal investigation and this time the public prosecutor opened formal investigations [48]. They were closed in April 2018 with a referral: The public prosecutor of Cologne found probable cause that Lothar Lingen was guilty of the crime of destruction of materials under official safekeeping [49] but decided to dispense public charges in the case that Lingen pays 3,000 Euros [50]. This decision was justified with the assumption that Lingen was already sufficiently penalized because of the public outrage about his destroying the files and the subsequent public interest in him.

f) NSU: no discursive event

Despite heavy media coverage of the NSU complex in recent years it did not have transformative power. The acts of the NSU were unanimously condemned, but there was no discussion about how far elements of the ideology of the NSU had filtered into mainstream society. The issue of structural racism within the police was raised but never became a dominating subject and was not even acknowledged by the parliamentary inquiry committees. After the NSU became known even some voices within the mainstream questioned the justification for the existence of a secret service that failed to detect a terrorist neo-Nazi organization that was able to commit so many crimes over a period of 12 years. But these voices were quickly silenced and the secret service was able to perpetuate the story that with more money, staff, and powers this would not happen again.

5. The case against Zschäpe and others before the Munich Court of Appeals [51]

Since the start of the trial on May 5th, 2013 there have been over 437 trial days, during which about 600 witnesses have testified. The closing arguments from the prosecution, the lawyers of the victims, the victims and their lawyers, and the defense lasted almost one year from July 2017 until the end of June 2018 (see 5.g). The trial has been one of the longest running in recent German history. However, considering the number of crimes, their seriousness and their complexity, the length is not unwarranted.

a) Overview of the court and the parties

Since May 6th [52], 2013, Beate Zschäpe and four other defendants have been standing trial before the Munich Court of Appeals [53] (Oberlandesgericht [OLG]). Amongst other charges Zschäpe is accused of founding the terrorist organization the NSU, complicity in ten murders and many attempted murders, complicity in 15 bank robberies, as well as aggravated arson and attempted murder committed as a direct perpetrator. She has not been charged with the bomb attack in Nuremberg in 1999, as it only became known during the trial that this attack had also been committed by the NSU. There are four male defendants standing trial alongside her. Ralf Wohlleben and Carsten S., two of her comrades from their time in Jena, are charged with supplying the Ceska 83 gun and silencer used in the murders and therefor aiding and abetting the nine murders in which the Ceska 83 had been used. Holger Gerlach, another comrade from their earlier years in Jena, is charged with having provided them with identity documents, thus supporting the terrorist organization NSU. Finally, André Eminger, a confidant from their time in Chemnitz and Zwickau, is being charged with helping Mundlos and Böhnhardt carry out the bomb attack in Cologne in January 2001 and two robberies by renting cars to be used in the crime. For these acts he is being charged with aiding and abetting attempted murder and aggravated robberies and supporting a terrorist organization.

Zschäpe faces life imprisonment, while Wohlleben and Eminger face prison sentences of up to 15 years and Carsten S. and Gerlach risk up to 10 years.

Zschäpe and Wohlleben have been in pretrial detention since November 2011. A third defendant, Eminger, was taken into detention on September 12th, 2017 due to a motion of the public prosecutor. Eminger had already been in detention awaiting trial in November 2011 but had to be released because of a judgment by the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof), as did Holger Gerlach and Carsten S. Now, in his closing arguments the federal prosecutor pleaded that Eminger be found guilty on all counts and be sentenced to 12 years in prison. Arguing that Eminger might flee because of the severity of the sentence, the prosecutor also moved for Eminger to be taken back into detention. After a hearing the court granted the motion and since then Eminger has been in detention. [54]

The five defendants are represented by 14 defense lawyers. Beate Zschäpe alone has four public defense lawyers, who were chosen by her but are paid for by the state. In addition, she has one lawyer whom she pays for herself.

The court chamber (senate) consists of five judges: The presiding judge Manfred Götzl is joined by four associated judges (Dr. Lang, Dr. Kuchenbauer, Odersky, and Kramer), and now only by one backup or substitute judge. The trial started with three backup judges, two of whom have already had to replace outgoing judges. This is important because in German criminal procedural law the presiding judge must have been part of the trial from the beginning, which means that if two more judges were to leave, the case the trial would collapse as no one would be able to replace them.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s office (Der Generalbundesanwalt [GBA]) is represented by three federal public prosecutors (Dr. Diemer, OStA Weingarten, OStAin Greger). In general, the federal prosecution has kept a very low profile during the trial.

The German Criminal Procedure Act [55] gives victims of certain crimes or family members of persons who have been murdered the right to join the proceedings as private accessory prosecutors (Nebenkläger). The victims who joined the proceedings as private accessory prosecutors have the right to be represented at trial by a lawyer (Nebenklägervertreter). Private accessory prosecutors and their lawyers have almost the same rights as the defendants and their lawyers. The over 95 private accessory prosecutors (victims or close family members of the murdered victims) are represented by approximately 60 lawyers. Most of these lawyers attend every trial day.

Courtroom A 101 has 100 seats for the public. Half of these seats have been reserved for the press; the other half is open to the general public. At the beginning of the trial, there was much media interest and the press seats were allocated on a first come, first served basis. All Turkish media outlets missed out on that scheme. After the Turkish daily newspaper Sabah obtained a judgment from the German Federal Constitutional Court [56], the Munich Court of Appeals had to allocate the press seats anew by way of a lottery system, with a certain number reserved for the Turkish press.

However, the huge media interest wound down very quickly. What is more, there have been hardly any reports of the case and the trial in the international press [57] other than in Turkish newspapers. With the exception of the early days of the trial, there have almost always been empty seats in the public gallery. There are no regular observers of the trial, with the exception of a handful of journalists and the NGO, NSU Watch [58]. The latter has set itself the task of taking records of every trial day, which it publicizes on its public website in German and with some records in Turkish and English [59].

The case file, which is made available to participants in the trial in electronic form, is huge: it contains about 900 folders averaging 300 pages each, and the electronic version amounts to over 50 GB of data.

b) German criminal procedure

German criminal procedure follows the inquisitorial system, as opposed to the adversarial system in the UK or US. There is no jury but instead the judge or, in this case, the presiding judge and four associate judges. The judges decide which evidence to examine and which witnesses to question. The judges have to search for the “truth” – even if a defendant confesses to the crime the judges still have to examine whether she or he actually did commit the crime. Therefore, there is nothing like a guilty plea (see para 5.d.dd). The judges are also the first to question the witnesses, followed by the prosecution, the private accessory prosecutors and their lawyers, and the defendants and defense lawyers. Parties to the proceedings (prosecution, defense, private accessory prosecutors) can bring motions to call witnesses or consider other evidence, which the court either grants or denies based on the rules of criminal procedure. More than 250 of these motions to take evidence were filed by the defense lawyers and victims’ counsels, some successfully, others not. Parties also have the right to make statements on each witness testimony or other piece of evidence. Also, each party has the right to file motions challenging the court for fear of bias. During the NSU trial the defense lawyers unsuccessfully filed 46 such motions.

The official trial record only contains formalities such as motions brought by parties or which witnesses were heard, but not what they have said. There is no audio or written record of the content of witness statements or the statements of other persons in the courtroom. Accordingly, all parties and the judges have to take their own notes, with no way to verify whether these are accurate. Therefore, there are frequent arguments about what certain witnesses have said.

This institution of private accessory prosecutors is also rooted in the inquisitorial system and something foreign to the adversarial criminal trials conducted in common law jurisdictions.

c) The federal public prosecutor and its indictment

aa) The indictment

The federal public prosecutor has been leading the investigations since November 11th, 2011 and indicted the five defendants on November 5th, 2012.

The prosecution has narrowed the scope of the case in its indictment, as it only charged five people and claimed that the NSU consisted of only three members, two of whom are dead. Furthermore, the other neo-Nazis supporting the NSU allegedly did not know the details of the crimes committed.

In addition, by not naming former informants of the secret service as witnesses, the federal prosecutor is trying to keep them out of the trial, even if they apparently have important knowledge regarding the defendants. The lack of discussion from the defense as to the role of the secret service and their attempts to disrupt investigations in that direction was then questioned by the victims’ families and their lawyers. As a result, the informants and the secret services have played a much larger role at the trial than the federal prosecutor intended. Several informants and their secret services officers have had to testify before the court.

This official narrative is being challenged by the lawyers for the victims’ families, who are trying to establish that Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe did not act alone, but were part of a network of neo-Nazis which aided and abetted them. For example, these accessories may have helped the NSU scout victims and locations for the bomb attacks in different cities all over Germany. The testimonies of Zschäpe and Wohlleben have shed no light on the network surrounding the NSU, as both were careful to protect others in their statements.

bb) Evidence

The public prosecution’s case against the five defendants is mainly built on circumstantial evidence. Two significant pieces of evidence are the statements of Holger Gerlach and Carsten S. However, these need to be complemented by a chain of circumstantial evidence, especially as both deny having had knowledge of the existence of the organization the NSU and of the murders. There are no witnesses who admit to having known of the NSU’s existence and of the murders it planned and carried out. At this stage of the trial, all of the important pieces of evidence have been examined and they have all confirmed the indictment. This circumstantial evidence consists, inter alia, of the following:

Regarding the existence of the terrorist organization NSU:

– The aforementioned video in which the NSU takes credit for the crimes.

– The aforementioned NSU letter, which was sent out to various neo-Nazi magazines and organizations, introduced the NSU and included donations to the addressees. This letter was written on the computers found in the wreckage of the apartment in Frühlingsstraße 26 used by the three NSU members.

Regarding the murders and bomb attacks:

– The video in which the NSU claimed responsibility for ten murders and two bomb attacks in Cologne. The police discovered video files used in the production of this video on the computers found in the wreckage of the apartment in Frühlingsstraße 26. Some of the video footage is made of photos from the crime scenes, which only the murderers could have taken.

– The murder weapon, a Ceska 83, was found in the apartment in Frühlingsstraße 26 in Zwickau that, according to the indictment, was set on fire by Beate Zschäpe on November 4th, 2011.

– The testimony of Carsten S. regarding the acquisition and the handing over of the Ceska 83 with a silencer and the bomb attack in Nuremberg in 1999.

– The service weapons of the murdered police officer and her colleague, which were found in the wreckage of the apartment in Frühlingsstraße. Sports pants with bloodstains from Michèle Kiesewetter were also found in the apartment. The pants were not washed after being stained.

– Video footage from surveillance cameras in Keupstraße around the time of the bomb attack showing Mundlos and Böhnhardt.

– Also found in the Frühlingsstraße 26 apartment were maps on which the crime scenes are marked, and a collection of newspaper articles regarding the murders with Zschäpe’s fingerprints.

– None of the murders was witnessed directly, but witnesses close to the crime scenes at the relevant times stated that they had seen two young white males, often on bikes.

Regarding the robberies:

– Video footage from surveillance cameras shows two persons of very similar age and build to Mundlos and Böhnhardt.

– Money was found in the hideout of the NSU members that could be traced to several of the robberies and still had the revenue stamp around it.

– Witnesses described the robbers as two young white males fleeing on bikes.

– Items of clothing, guns etc. were found in the Frühlingsstraße apartment, which look exactly like items worn and carried by the robbers seen in the surveillance footage.

d) The defense and the defense strategy

aa) Defendant André Emigner

Only the defendant André Eminger has remained silent for the trial. His strategy was built on the assumption that the evidence before the court would not be sufficient to find him guilty of aiding and abetting a murder and supporting a terrorist organization. Even though he remained silent, he made it clear by the way he behaved and the clothes he wore that he was convinced national socialist.

It became clear that his strategy had not worked when he was taken into pretrial custody in September 2017 because the court saw strong grounds to suggest that he had committed the crimes.

bb) Defendant Holger Gerlach

Holger Gerlach had already testified during the investigative phase and his statement had led to Ralf Wohlleben und Carsten S. as those who had supplied the Ceska 83 murder weapon. During the trial his lawyers only read a written statement in which the repeated what he had told the police. He did not answer any questions. The strategy was obvious: he claimed he had left the neo-Nazi scene and he only faced a sentence up to 10 years. It was clear he was facing a reduced sentence because his testimony had helped to uncover who had supplied the murder weapon. By answering questions and making statements he could have risked incriminating himself further, since there was no clear evidence that he had indeed broken with neo-Nazi ideology.

cc) Defendant Carsten S.

After Holger Gerlach’s testimony had led the police to him, Carsten S. also cooperated with the police. In contrast to Holger Gerlach, Carsten S. had left the neo-Nazi scene a long time before, and now lived as an openly gay man doing social work. Much more than Holger Gerlach, he told the police what he knew, even if it took a long time for him to tell most of what he had done and knew in connection with Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe, the NSU, and the NSU’s crimes. From the very beginning of the trial he testified fully and let the victims’ counsel question him for several days. Since he was a youth in the German legal sense (Heranwachsender) at the time he supplied the murder weapon, he only faces up to 10 years in prison for aiding and abetting nine murders.

dd) Defendant Beate Zschäpe and her testimony of December 2015

Defendants in criminal cases in Germany do not have to plead guilty or not guilty. Furthermore, German criminal procedure law allows defendants to speak in their defense at any time and in any way they chose during the trial. Defendants are not required to speak for themselves, but can let their lawyer speak for them and authorize what they say subsequently. Accordingly, there are no sanctions for defendants who lie to the court. However, a defendant’s statement does not have the same status as a witness testimony and the court can dismiss whatever the defendant brings forward if it does not correlate with the other evidence and the court deems it a false.

From the first day in police custody Beate Zschäpe made it clear that she wanted to explain herself and speak. Yet it was the strategy of her first three lawyers for her to remain silent during the trial, to which she agreed. Accordingly, she made no statement until the 249th day of trial. Her lawyers maintained that the evidence was not sufficient to find her guilty of being a member of a terrorist organization and of the (attempted) murders.

The victims and victims’ families had often said they wanted her to speak and to attempt to explain to them exactly what happened. Why were their husbands and brothers picked out by the NSU as victims? Were there supporters near the respective crime scenes who helped to choose the victims and aided and abetted the members of the NSU? How extensive was the NSU’s support network? Did the NSU have contact with neo-Nazis in other European countries? What contact did the members and supporters of the NSU have with secret service informants and how much did these informants know about the members and supporters of the NSU?

For a long time it seemed that Zschäpe agreed with the strategy of her lawyers. However, from the middle of 2014 it became clear that she was growing unhappy with her lawyers and their strategy of her remaining silent [60]. Subsequently, she tried everything to get rid of her three old lawyers, which is very difficult under German criminal procedure law as the lawyers were appointed as public defense lawyers. Her aim was to get a new lawyer who would help her draft a defense statement. Finally, in the summer of 2015 she was able to persuade the court to assign her a fourth public defense lawyer of her choice. On December 9th, 2015, this new lawyer read her prepared statement during triall [61].

As it was the first time in four years that the main defendant would make a statement and as it was expected that she would be able to shed light on the aforementioned questions, expectations and hopes ran high. The media interest was almost as intense as it had been during the first days of trial. Some of the victims and victims’ families also attended the trial on the day of her statement.

It took her lawyer only about two hours to read Zschäpe’s statement and to make it obvious that she was not willing to provide answers to the open questions. Rather her statement was poorly assembled and it was hard to comprehend what she and her lawyers had hoped to accomplish with it.

She claimed in her statement that only the two dead men, Uwe Mundlos and Uwe Böhnhardt, had planned and committed the murders and the bomb attacks. She did not know of an organization called the NSU and only found out about its crimes after they had been committed. She was supposedly horrified by the crimes but unable to stop the two men she was living with. As she was supposedly emotionally and financially dependent on them, she was unable to leave them and turn herself in. In her statement she tried to paint a picture of an ignorant, emotionally and financially dependent housewife of two terrorists. For example, she claimed Mundlos and Böhnhardt built the bomb while she was out running and therefore did not notice anything. This is a common stereotype for the wives of neo-Nazis, and Zschäpe tries to use it to her advantage.

However, her plan did not succeed. During the trial many witnesses testified that she was a convinced neo-Nazi who had played an active part in the neo-Nazi organizations in Thuringia before the trio went underground. Many also confirmed the impression of her during the trial as being a confident woman capable of handling the two men and standing her ground. Most observers of the trial are sure that Zschäpe’s statement has not helped her defense at all and do not find the story credible. Nonetheless, she provided confirmation of many details for which there was previously only circumstantial evidence. Her denial of having knowledge of the organization and its crimes was an obvious and unfounded assertion, designed solely to avert the prosecution’s claim that she was a member of the NSU and had aided and abetted its crimes by camouflaging their operation and providing it with a credible facade. Accordingly, the media coverage was crushing and the victims were appalled that she not only answered none of their questions but had the audacity to apologize to them. Almost in the same breath her lawyer read the apology and said that Zschäpe would not answer questions from the lawyers of the victims and the prosecution but would only answer questions by the court and other defense lawyers in writing. This lead the court to dictate its questions to Zschäpe’s lawyer and he provided the answers a few weeks later. So far, the answers have been almost as meaningless and evasive as her main statement and only confirmed what witnesses had testified before [62]. The court went through this circle a few times until all the questions it had were answered. In the early summer of 2016, after the court had finished with its questions the victims and their lawyers finally had the chance to ask questions themselves. Even if Zschäpe had said she would not answer their questions they took the chance and emphasized how many questions she had not answered. The victims’ lawyers had altogether more than 300 questions, which they directed at her and read aloud [63]. Zschäpe stated that she would only answer the questions the court adopted as its own. However, very few of these questions were taken up by the court and put to Zschäpe. The vast majority of the victims’ questions have gone unanswered.

It is most likely that Zschäpe’s strategy will not work. Her statement was so implausible and not in line with the facts established during the trial that she will most likely be found guilty on all counts.

ff) Defendant Ralf Wohlleben

The strategy of Wohlleben from the very beginning was to present himself as a convinced “nationalist” and “ethno-pluralist” by claiming that he was not a racist, did not know his old friends had founded the NSU and had only helped to find a weapon for them in case they needed it to commit suicide and that this weapon was not the murder weapon. For the first two years he remained silent. But since Beate Zschäpe had broken her silence he also decided to testify on December 16th, 2015 [64]. He also prepared a written testimony, read it out himself, and answered questions from the other parties of the trial personally. Despite this, like Zschäpe, he did not reveal any previously unheard information and thus did not shed any new light on the case.

Wohlleben admitted that he had a part in obtaining the pistol with a silencer, which was brought to Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe by the defendant Carsten S. However, he alleged he did not know that the three had founded the terrorist organization the NSU and planned to commit murders and bomb attacks. He claims he assumed that the weapon was only to be used to commit suicide if the police found them. He tried to paint a picture of himself as a victim of the political left and the state, as he is being prosecuted solely for his right-wing ideas. Unlike Zschäpe, who gave no information about her political stance and claimed she had no interest in politics after going underground, Wohlleben openly admitted his right-wing views and activism. However, he claimed to have always rejected violence. His statement, too, was seen to lack credibility and to conflict with the evidence. Furthermore, the statement was only provided after 250 days of trial, during which time he had listened to all the other testimonies. Witnesses testified that he shared the same radical views as the three alleged NSU members and knew about the bombs in the garage and the robberies.

The much-anticipated testimonies have not helped to provide answers to the greater questions, and therefore the parliamentary committees will have to continue with their work.

e) The victims: private accessory prosecutors

The family members and the victims who had joined the proceedings as private accessory prosecutors formed a very diverse group: a random group, since the victims were selected randomly. Accordingly, they had different interests in the trial and different ideas what their lawyers should do and how they should do it. Despite all the differences the overwhelming majority of the victims and their counsels fought for more answers. They wanted to know:

– Why and how were their loved ones singled out as murder victims; were local neo-Nazis involved in the process, did they pass the information on?

– How big was the NSU and its network, and are its members and supporters still active today?

– Could the crimes have been prevented by the intelligence the secret service disposed of? If this intelligence had been passed on to police, could it have led to the arrest of Mundlos, Böhnhardt, and Zschäpe before they even started with their murder campaign?

Despite their numbers, the presence and the voices of the victims and their families (most of whom are also private accessory prosecutors) have not been felt or heard loudly at trial. Only members of fours families (Taşköprü, Kılıç, Kubaşık Yozgat) who had lost their husbands, fathers or sons or daughter to the NSU were heard as witnesses during the trial. Only members of the four named families had the chance to testify and speak about their suffering in the wake of the murders and the subsequent police investigations. The others only had the chance to talk about this in their closing arguments.

After the first days of the trial it also became clear that it was emotionally stressful for the victims’ families to regularly participate in the proceedings. Many of them now abstain from this. The lawyers representing the victims have so far been unsuccessful in making the structurally racist investigations an issue. But at least they were able to raise the above-mentioned questions in regard to the supporting network of neo-Nazis and the role of secret service. This was achieved by their lawyer filing a motion for evidence, e.g. to hear certain witnesses from the secret service or their former informants and by making statements after witnesses were heard.

f) Witnesses

Many of the neo-Nazi witnesses and the secret service officials gave frequently and sometimes brazenly false testimonies in court. Whether or not they will be investigated and brought to trial on perjury charges is currently unknown, as perjury charges are usually only brought after the conclusion of the trial in which the witness had testified. This leaves the impression that they are able to lie in court without any repercussions, thus encouraging other neo-Nazi witnesses to follow their example.

g) Closing arguments

aa) Federal public prosecutor

The federal public prosecutor pleaded on eight days between July 25th, 2017 and September 12th, 2017. [65] They asked for the following sentences:

- Beate Zschäpe: Life imprisonment and to find that the crimes carry a particularly heavy burden of guilt, meaning that she has no chance of being released after 15 years.

- André Eminger: Twelve years’ imprisonment.

- Holger Gerlach: Five years’ imprisonment.

- Ralf Wohlleben: Twelve years’ imprisonment.

- Carsten S.: Three years’ imprisonment without parole.

bb) The private accessories and their counsels

The private accessories (the victims), and their counsels pleaded from November 15th, 2017 to February 8th, 2018. [66] Eight family members of the murdered and casualties of the bomb attacks and more than 40 counsels pleaded. Despite all differences in content and length of their statements the private accessories and their counsels tried to show the extent of suffering they had been through on account of the loss of a loved one and the accusations of the police. They also stated that their clients were not convinced by the official version of an isolated NSU without a wider support network in the cities where the murders had taken place. They showed this in great detail, also demonstrating why the official version was not plausible and did not fit to all known facts that pointed in a different direction.

cc) The defense

The defense pleaded from April 24th to June 20th, 2018. Their pleadings were:

- Beate Zschäpe: Acquittal regarding the main counts and a sentence regarding only the robberies of not more than ten years.

- André Eminger: Acquittal. Eminger let his lawyers state for him that he is a “National Socialist” and that the other defendants and witnesses who had died being National Socialists themselves had not stated the truth.

- Holger Gerlach: A maximum sentence of two years without parole.

- Ralf Wohlleben: Acquittal. The lawyers of Ralf Wohlleben also used their closing argument to disseminate racist and neo-Nazi propaganda – both openly and partially concealed.

- Carsten S.: Acquittal; he admitted to the delivery of the murder weapon but alleged that he did not know they needed the weapon for racist murders. At least two of his lawyers are known for having been or being active members of the right-wing scene.

Judged by the findings during the trial it is most likely that the court will find the defendants guilty on all counts.

6. Summary and outlook

To summarize what happened after the crimes of the NSU came to light:

- So far, only five people are standing trial for the crimes of the NSU and are most likely to be found guilty and sentenced after 437 days of trial.

- At the same time, it is unclear if the federal prosecutor will charge any of the nine supporters whose cases are still under investigation. Rather, he might try to close the cases once the judgment is final. As there is no official trial record it is left to the antifascist group NSU Watch to document the trial and write thorough protocols of each trial day.

- Law enforcement and the secret service agencies have been involved in a cover-up and the main question regarding their role is still unanswered. Despite strong criticism, the obvious involvement in aiding and abetting the neo-Nazi scene, and unresolved question of what the service actually knew about the NSU, the secret service emerged as one of the “winners” from the course of events, as they were given more responsibility and money. Up to now, there is only one case in which a criminal investigation has been opened against a former secret service worker for destroying files.

- The scope and intensity of the work of the 13 parliamentary inquiry committees have been and are very different. Some have played and are playing an important part in gathering information and shedding light on some of the most pressing questions. However, even these have often fallen short in their findings with regard to structural racism within law enforcement agencies and in clarifying the involvement of the secret services. Accordingly, no changes have been made in regard to the way racist and neo-Nazi crimes are being handled by the police, and often the political aspect of these crimes are played down [67].

- Investigative journalists have played an important part in investigating certain aspects of the NSU case and writing about otherwise classified information. Newspapers and TV have covered the trial thoroughly [68] and many prime-time documentaries and series have been broadcast. Yet some media outlets used racist stereotypes when writing about the victims and depoliticized the crimes by focusing on the psychology of the defendants, especially of Beate Zschäpe, her looks, her struggle with her lawyers, and her behavior during the trial, whilst using sexist clichés [69].