A self-professed Golden Dawn member stabbed leftist rapper Killah P to death in Piraeus four years ago on September 18.

Piraeus, Greece – Magda Fyssas walks to the corner of her living room and lights four crimson-coloured candles. She places them next to a smaller, already-lit white candle under a large charcoal sketch of her son, an anti-fascist rapper who was killed by a self-professed Golden Dawn member four years ago.

In the memory-filled home she says now feels empty, she does this every day.

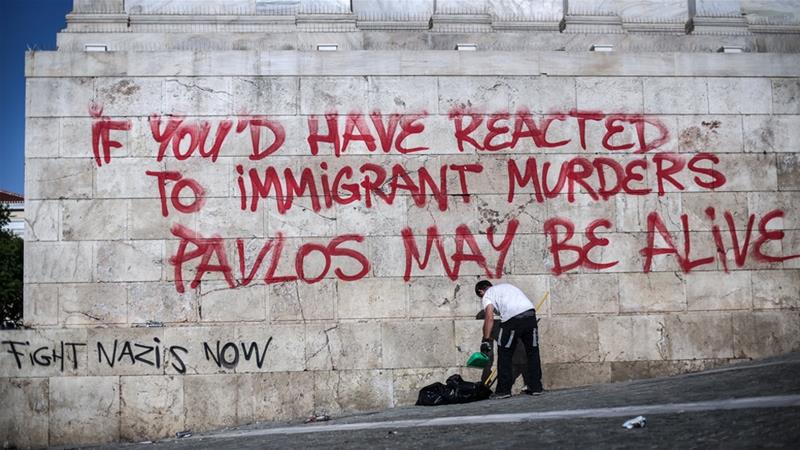

The murder of 34-year-old Pavlos Fyssas on September 18, 2013, ignited weeks of anti-fascist protests, clashes with riot police and altercations with Golden Dawn, the neo-fascist party that holds 17 seats in Greece’s parliament.

Protesters rally in cities across the country every year on the anniversary of his death, mourning Pavlos and other victims of far-right violence.

His murder was a turning point for the anti-fascist movement, which has since elevated Pavlos, whose rap name was Killah P, to martyr status.

In the working-class neighbourhood of Keratsini, a large monument depicting Pavlos rapping sits not far from his mother’s home. Throughout Athens, Piraeus and elsewhere, his name is tagged on buildings and pavements, his face emblazoned on posters.

Magda’s living room is her personal shrine to Pavlos, the wall covered in photos, posters and paintings of him.

In one photo, Pavlos wears a billowy black wig for Apokries, a Greek holiday akin to Halloween. In another, he squats with crossed arms and mimics the American hip hop group Run DMC, wearing a white jumpsuit and a large gold chain.

|

| Magda Fyssas sits in her living room gazing at a corner dedicated to her late son in September 2017 [Nick Paleologos/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

In a drawer under the photos, Magda keeps Pavlos’ letters and journal entries. She shuffles through the papers silently until she finds the one she is searching for: an entry titled “Alcoholic Anthology”.

“If all of your life is eaten away by fear of the familiar and unfamiliar,” the hand-written entry reads, “then death will find you fearful and sweaty, floundering and begging for mercy and more time, still harbouring the illusion that something might change at the last moment.”

Magda speaks comfortably about the political implications of her son’s murder and boldly about Golden Dawn, who she decries as “neo-Nazis” and “criminals”. But when asked about Pavlos’ character, her mood turns sombre and her expression severe.

“You’re asking a mother about what kind of a person her son was,” she says, her voice growing shaky. She pauses, lights a cigarette, takes a deep draw from it and, after a few moments, settles on a description of her son: “He was a free man.”

The murder

Pavlos spent the hours leading up to his murder in a cafe with a group of friends, among them his partner, watching a local football match on television.

After they left the cafe to head for another, an altercation occurred. The exact details of the incident remain disputed, but police were called to the scene. Pavlos had been stabbed. He was taken to hospital, where he later died.

His family, friends and some witnesses say that a group of far-rightists confronted Pavlos and his companions. Pavlos fought them off while his friends escaped, they say.

Magda learned that her son had been injured from Pavlos’ father. She rushed to the hospital, where a doctor told her that he had died of stab wounds. “I didn’t want to believe [it],” she says softly.

|

| Giorgos Roupakias, who admitted to killing Pavlos Fyssas, photographed in court on October 2, 2015 [Menelaos Myrillas/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

Giorgos Roupakias, who worked in the cafeteria at a Golden Dawn office and publicised his support for the party, was arrested for the murder. He later admitted to killing Pavlos. Last year, he was released from pre-trial detention and placed under house arrest. Golden Dawn denied any direct connection with the incident, although Nikolaos Michaloliakos, the founder and leader of the party, has stated that it accepts “political responsibility” for the murder.

“With regards to political responsibility for the murder of Fyssas in Keratsini, we accept it,” he said during a 2015 radio interview. “As for criminal liability, there isn’t any. Is it right to condemn a whole party because one of its followers carried out a condemnable act?”

In the months leading up to his death, Pavlos and his mother had regularly discussed the rise of Golden Dawn, which had transformed from an obscure band of hardliners flirting with Nazi imagery to a parliamentary party equipped with a paramilitary carrying out raids and attacks in neighbourhoods with a large number of immigrants.

Just a year earlier, in 2012, Golden Dawn entered the Greek parliament for the first time after securing 21 parliamentary seats and some seven percent of the vote. The sudden explosion of support for the party sent chills through much of Greek society, including the Fyssas family.

While walking together in their historically left-wing neighbourhood four months before the murder, Magda and Pavlos witnessed a flag-flying motorcade of Golden Dawn members parading through Keratsini.

“We didn’t feel safe,” she remembers, crushing a cigarette into an ashtray she balances in her lap. “We knew something bad was on the way, but I couldn’t have imagined it would impact my family directly.”

Following Pavlos’ murder, police arrested 69 Golden Dawn members, including the party’s senior leadership, who were subsequently charged with operating a criminal organisation.

At the time of publication, Golden Dawn’s press office had not replied to Al Jazeera’s request for a comment.

|

| In September 2017, Athenians walk past posters calling for protests to commemorate Pavlos’ murder [Nick Paleologos/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

Electra Alexandropoulou of Golden Dawn Watch, a group that monitors the party, says the trial will determine the future of the party and whether its offices and operations will eventually be shuttered.

The bulk of the evidence suggests that the attack on Pavlos – as well as similar attacks on immigrants and political opponents – were carried out with the knowledge and approval of high-ranking Golden Dawn officials.

If the senior cadre isn’t convicted, she argues, the court will effectively send a message that Golden Dawn enjoys impunity. “If you know someone has coordinated a murder and you let him go free, what message are you giving him? That he’s welcome to do it again.”

Anti-fascist outrage

Petros Constantinou is a city councillor and the national director of the Movement Against Racism and the Fascist Threat, known as Keerfa. Sitting in his fifth-floor office, he recalls the moment a fellow activist called to inform him of Pavlos’ death.

Petros and other left-wing organisers sprang into action. The local media was reporting that the killing was the result of a football rivalry, but within five hours Keerfa and a broad alliance of left-wing groups had released a statement pointing the finger at Golden Dawn.

|

| Petros Constantinou attends a pre-election rally in September 2014 [Aris Oikonomou /SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

Weeks of demonstrations ensued, with tens of thousands of Greeks swarming streets across the country, particularly in the capital.

“For us, it was very clear,” Petros says. “We don’t let the Nazis have any space in the streets, in the media, in the parliament, anywhere.”

Protests turned into violent clashes with the police. Golden Dawn’s opponents demanded the immediate closure of the party.

“This is not a political party,” Petros says. “This is a Nazi, criminal group … and we cannot accept them as part of a democratic [system] because they don’t respect democracy.”

Just weeks after the murder of Pavlos, gunmen shot and killed two Golden Dawn members outside the party’s office in the Neo Irakleio area of the capital.

Commemorations of the murder of Pavlos and the 2008 police killing of 15-year-old Alexandros Grigoropoulos serve as “forms of communication” for anti-fascists and the broader anti-authoritarian movement, says Nicholas Apoifis, the author of Anarchy in Athens.

“It’s quite a legitimate mourning of the past,” he explains. “But there is no way to get around the fact that the images of Fyssas and Grigoropoulos are used to convey … anger and to galvanise the [anti-fascist] space. They are ways of articulating politics, of articulating resistance and of articulating emotional responses to events as well.”

It has been more than two years since the start of the Golden Dawn trial, which involves 69 defendants and will rule on the legality of the organisation itself. Slated to conclude in 2018, it has progressed slowly, largely owing to the complexity of the case.

More than 1,100 documents about alleged crimes committed by party members and officials must be examined during the trial, while hundreds of witnesses must testify.

|

| Demonstrators rallied in Keratsini on the first anniversary of Pavlos’ murder on September 18, 2014 [Nick Paleologos/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

Many of the testimonies paint a picture of premeditated violence by Golden Dawn members, and some witnesses have touched all too close to home for the Fyssas family. “The knives will come out after the elections,” one party member said, according to the testimony of filmmaker Konstantinos Georgousis, who followed party candidates during the run-up to the 2012 elections in the documentary The Cleaners.

Earlier in the trial, Violetta Kougatsou, who testified as a witness to Pavlos’ murder, told the jury that police were already present at the time of the attack: “Pavlos died helplessly, killed in front of the police. These policemen did not represent the Greek people.”

Police have provided varying explanations of the night’s events, some of which purport that officers were unable to intervene due to a mob of club-wielding far-rightists who had assembled and others that claim the officers arrived after the stabbing took place.

‘Beginning of the end for fascism’

Javed Aslam immigrated from Pakistan to Greece in 1996, a time when he says there was little anti-immigrant violence in the streets. Occasionally slapping the wooden desk in front of him in his Athens office, Javed recalls the explosion of violence that hit the Pakistani migrant labourer community between 2010 and 2013.

Behind Javed, who is now the president of the Pakistani Community in Greece, a union for migrant workers, is a sticker. “Smash the neo-Nazis,” it reads in Greek.

|

| Javed Aslam, president of the Pakistani Community in Greece, in his office in September 2017 [Nick Paleologos/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

He recalls scenes of violence from that period: Golden Dawn members would enter busses full of Pakistani labourers and assault them in broad daylight, he says, adding that such attacks rarely elicited a response from Greeks and the media.

In January 2013, nine months before Pavlos was killed, a pair of Golden Dawn-affiliated assailants stabbed to death Shahzad Luqman, a 26-year-old Pakistani who was on his way to work.

“This was a very, very difficult day… [for all] immigrant communities – not just Pakistanis,” Javed says. “That was when you saw that no one is going to help you… people were thinking that no one is safe here, that there [are] no laws and rights for immigrants.”

Facing political pressure and criminal charges that could render the organisation extinct, Golden Dawn has since attempted to re-brand its image as a legitimate nationalist party, abandoning much of the public displays of Nazi-like salutes and scaling back the street-level violence.

The attacks have not come to a complete standstill, though, and the mass influx of tens of thousands of refugees and migrants in recent years has been accompanied by a wave of violence targeting camps and asylum seekers.

On Chios Island, anti-refugee violence has become part and parcel of life in the refugee camps. In May, an unspecified number of alleged Golden Dawn members beat and injured dozens of Pakistani labourers in Aspropirgos, located near the capital, according to local media reports.

|

| Hussein Luqman (right), Shahzad Luqman’s father, attends the unveiling of monument for Pavlos Fyssas on September 18, 2014 [Nick Paleologos / SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

For Javed, the murders of Pavlos and Shahzad represent a turning point in the struggle against Golden Dawn, while providing a shared rallying cry for Greeks and immigrants alike.

“If we [don’t] remember them, it means we will let them down,” he says. “They give us [a way] to be together in the fight against fascism. The murders of Fyssas and [Luqman were] the beginning of the end for fascism.”

Expecting death?

Athanasios Perrakis, a 34-year-old Greek rapper whose stage name is Tiny Jackal, was in the E-13 hip hop crew with Pavlos. He remembers the slain rapper as his mentor and one of his closest friends.

On a warm September afternoon, he hops in his silver 4WD and sets off from his native Keratsini for Athens. The American rapper Big Pun blares through his sound system.

On his left arm are tattoos of his favourite rap artists: 2Pac, Run DMC, Redman and others. On his hand are Pavlos’ logo and the date of his death. “This is so I don’t forget,” he says.

|

| Athanasios Perrakis, known as Tiny Jackal, stands in the Exarchia neighbourhood of Athens in September 2017 [Nick Paleologos/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

He weaves through Keratsini’s narrow back alleyways, passing graffiti of hammers-and-sickles, anti-fascist declarations and calls for working-class revolution.

Once in Athens, he stops at a red light near a crowded intersection. Plastered on a wall are posters announcing two demonstrations.

The first is slated for September 16 outside the US Embassy in Athens and bears Pavlos’ face superimposed next to that of an American anti-fascist who was murdered by a neo-Nazi in Charlottesville, Virginia, last month. “Four years since the murder of Pavlos Fyssas,” it reads. “One month since the murder of Heather Heyer in the US. From Greece to America, smash the neo-Nazis.”

The other will be held on September 18. “Close the offices of the neo-Nazis,” it proclaims.

Athanasios recalls his last meeting with Pavlos, a few days before he was killed. They discussed creating a Piraeus-based crew that would function as a Greek rendition of the Wu Tang Clan, he reminisces.

After the murder, Athanasios recorded a tribute album for Pavlos. But after being accused of attempting to profit from his friend’s death, he retreated into depression for a while.

Four years later, he says he still struggles to cope with the loss. He is overwhelmed with emotions when he hears Pavlos’ songs blasting from a passing car or sees images of his friend on the walls of his hometown, he explains.

|

| Athanasios shows a hand tattoo he got to remember Pavlos Fyssas, September 2017 [Nick Paleologos/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

One of Pavlos’ songs – titled “Zoria”, which translates imprecisely to “hard times” – haunts Athanasios until today.

A day like this is a good one to die,

Gracefully and on public display.

My name is Pavlos Fyssas from Piraeus,

Greek – whatever that means,

Not a flag, a black-shirted

Spawn of Achilles and Karaiskakis.

For Athanasios, these lyrics suggest that Pavlos suspected he might be killed by neo-fascists, who are notorious for dressing in black and waving Greek flags. He points to Golden Dawn’s ultra-nationalism and the view that they carry the legacies of Greek mythological heroes like Achilles and nationalist figures such as Georgios Karaiskakis, the military leader who commanded battalions in the fight against Ottoman rule in the 19th century.

‘To be continued’

In the weeks leading up to the killing, Athanasios says tensions hit a fever pitch in Keratsini. Among the clashes between anti-fascists and Golden Dawn members that is seared into his memory is an instance in which the latter beat a group of communist union organisers for hanging anti-fascist posters in the neighbourhood just days before Pavlos’ killing.

Emphasising the political nature of the violence, Athanasios nonetheless says he regrets the widespread reduction of Pavlos to an anti-fascist musician. “So many people focus on the songs about his anti-fascist actions,” he says, frustrated. “Pavlos was not only that, although he was [an anti-fascist]. He had songs about friendship, family, life and what to do with society. He was the type of person who would help you with anything.”

|

| Magda sits in front of the memorial of Pavlos Fyssas on September 17, 2016 [Alexandros Michailidis/SOOC/Al Jazeera] |

Back in her home, Magda says her family will continue to fight despite feeling that no legal measures will provide justice for the loss of her son. “What we do is for everyone who is still out there,” she maintains. “Like we lost Pavlos, someone else may be killed in the same way.”

She concludes: “Pavlos died as a free man who tried to kill fear that night… He stayed back to defend his friends, and he may have known that it would cost him his life.”

She lights another cigarette and points again to her son’s journal entry sitting on the coffee table. “Never underestimate the heart of a free man,” the note exclaims. “I hope for nothing, I fear nothing, and I am free. This is exactly why I am not afraid to die now – because I will keep on living, and that’s your biggest fear.”

At the bottom, it reads: “To be continued.”